|

Clan MacKenzie |

|

|

|

The progenitor of the Gerloch of Gairloch branch of the Mackenzies

was, as above shown, Hector, the elder of the two sons of Alexander, seventh

chief, by his second wife, Margaret Macdowall, daughter of John, Lord of

Lorn. He lived in the reigns of Kings James III and IV and was by the

Highlanders called "Eachin Roy", or Red Hector, from the colour of

his hair. To the assistance of the former of these monarchs, when the

confederated nobles collected in arms against him, he raised a considerable

body of the clan Kenzie, and fought at their head at the battle of

Sauchieburn. After the defeat of his party, he retreated to the north, and,

taking possession of Redcastle, put a garison in it. Thereafter he joined the

Earl of Huntly, and from James IV he obtained in 1494 a grant of the lands

and barony of Gerloch, or Gairloch, in Ross-shire. These lands originally

belonged to the Siol-Vic-Gilliechallum, or Macleods of Rasay, a branch of the

family of Lewis; but Hector, by means of a mortgage or wadset, had acquired a

small portion of them, and in 1508 he got Brachan, the lands of Moy, the

royal forest of Glassiter, and other lands, united to them. In process of

time, his successors came to posses the whole district, but not till after a

long and bloody feud with the Siol-Vic-Gilliechallum, which lasted till 1611,

when it was brought to a sudden close by a skirmish, in which Gilliecallum

Oig, laird of Rasay, and Murdoch Mackenzie, a younger son of the laird of

Gairloch, were slain. From that time the Mackenzies possessed Gairloch

without interruption from the Macleods. |

|

BADGE: Cuilfhion (hex aquifolium) holly.

This last writer proceeds to tell how Cailean acquired the coat of

arms first used by the Mackenzie chiefs. The King, it appears, was hunting in

the forest of Mar, when a furious stag, brought to bay by the hounds, made

straight at him, and he would doubtless have been slain had not Cailean

Fitzgerald stepped in front of him, and shot the beast with an arrow through

the forehead. For this, it is said, the King granted him for arms a stag’s

head puissant, bleeding at the forehead, on a field azure, supported by two

greyhounds, with, as crest, a dexter arm bearing a naked sword, surrounded

with the motto "Fide parta, fide aucta." At a later day the

Mackenzies changed this crest and motto for those of the MacLeods of the

Lews, to whose possessions they had succeeded in that island. According to the Earl of Cromarty, Cailean Fitzgerald married a

daughter of Kenneth MacMhathoin, the Mathieson chief, and had by her one son

whom he named Kenneth after his father-in-law. Cailean was afterwards slain

by MacMhathoin out of jealousy at the Irish stranger’s succession to his

ancient heritage, and it was from the son Kenneth that all the later members

of the family and clan took their name MacKenneth or Mackenzie. Cosmo Innes, however, in his Origines Parochiales Scotiae, vol.

ii, pp. 392-3, points out that the original charter on which this

Norman-Irish descent is founded does not exist, and is not in fact genuine,

and Skene in his Celtic Scotland, quoting an authenic Gaelic MS. of

1450, printed with a translation in the Transactions of the lona Club, shows

the Mackenzies to be descended from the same ancestor as the old Earls of

Ross. Their common ancestor, according to the MS. genealogy of 1450, was a

certain Gillean of the Aird, of the tenth century. Mr. Alexander Mackenzie,

author of the latest history of the clan, quotes unquestioned Acts of

Parliament and charters to show that the lands of Kintail, with the Castle of

Eileandonan, were possessed by the Earls of Ross for a hundred years after

the battle of Largs. It seems reasonable that the Mackenzie chiefs, as their

near relatives, were entrusted with the lands and castle at an early date,

and in any case there is a charter to show that the lands of Kintail were

held by Alexander Mackenzie in 1463. The first chief of the clan who appears with certainty in history is

" Murdo filius Kennethi de Kintail" who obtained the charter from

David II. in 1362. According to tradition, filling out the Gaelic genealogy

of 1450, the name of the clan was derived from this Murdoch’s

great-grandfather, Kenneth, son of Angus. This Kenneth was in possession of

Eileandonan when his relative William, third Earl of Ross who had married his

aunt, in pursuit of his claim to the Lordship of the Isles, demanded that the

Castle be given up to him. The young chief, however, refused, and, supported

by his neighbours the Maclvers, Macaulays, and other families in Kintail,

actually resisted and defeated the attacking forces of the Earl. He married a

daughter of Macdougall of Lorne, and granddaughter of the Red Comyn slain by

Bruce at Dumfries, but his son Ian, who succeeded him in 1304, is said to

have taken the part of Robert the Bruce, and actually to have sheltered that

monarch for a time within the walls of Eileandonan. He is said to have fought

on Bruce’s side at the battle of Inverury in 1308, and to have waited on the

King at his visit to Inverness in 1312, and he also led a following said to

be five hundred strong of the men of Kintail at the battle of Bannockburn,

three years later. His loyalty to Bruce is better understood when it is known

that he was married to Margaret, daughter of David de Strathbogie, Earl of

Atholl, the warm supporter of that monarch. Ian’s son, Kenneth of the Nose, had a severe struggle against the

fifth Earl of Ross. According to Wyntoun’s Chronicle, Randolph, Earl of

Moray, paid a visit to Eileandonan in 1331, for the punishment of misdoers,

and expressed himself as right blythe at sight of the fifty heads "that

flowered so weel that wall," but whether the heads were those of

Mackenzies or of Ross’ men we do not know. In 1342 the Earl of Ross granted a

charter of Kintail to a son of Roderick of the Isles, which charter was

confirmed by the King, and in 1350 the Earl actually dated a charter at

Eileandonan itself, from which it may be gathered that he had seized the

castle. Finally, the Earl’s men raided Mackenzie’s lands of Kinlochewe;

Mackenzie pursued them, killed many, and recovered the spoil; and in revenge

the Earl had him seized and executed at Inverness, and granted Kinlochewe to

a follower of his own. Mackenzie had married a daughter of MacLeod of the Lewis, and on his

execution his friend Duncan Macaulay of Loch Broom sent Murdoch, his young

son and heir, to MacLeod for safe keeping, and at the same time prepared to

defend Eileandonan against the attacks of the Earl of Ross. He kept the

castle against repeated attacks, but a creature of the Earl’s, Leod

MacGilleandreis, the same who had procured the death of the late chief, and

had received a grant of Kinlochewe, laid a trap for Macaulay’s only son, and

murdered him. At last, however, the young chief Murdoch, having grown up a

strong brave youth, procured one of MacLeod’s great war galleys full of men,

and with a friend, Gille Riabhach, set sail from Stornoway to strike a blow

for his heritage. Landing at Sanachan in Kishorn, he marched towards

Kinlochewe, and hid his men in a wood while he sent a woman to discover the

whereabouts of his enemy. Learning that MacGilleandreis was to meet his

followers at a certain ford for a hunting match, Murdoch fell upon him there,

and overthrew and slew him. He afterwards married the only daughter of his

brave friend and defender Macaulay, and through her succeeded to the lands of

Loch Broom and Coigeach. Then, after the return of David II. from his

captivity in England, he obtained in 1362 a charter from that monarch

confirming his rights, and he died in 1375. He was known as Black Murdoch of

the Cave, from his resort to wild places for security during his youth and

while laying his plans for the overthrow of his enemies.

His son, Murdoch of the Bridge, got his name from a less creditable

incident. His wife having no children, and he being anxious to have a

successor, he had her waylaid at the Bridge of Scatwell, and thrown into the

river. She, however, managed to escape, and made her way to her husband’s

house at Achilty, coming to his bedside, as the chronicler puts it, " in

a fond condition "; whereupon, pitying her case and repenting of the

deed, he took her in his arms. A few weeks afterwards she gave birth to a

son, and they lived together contentedly all their days. Murdoch was one of

the sixteen Highland chiefs who took part under the Earl of Douglas at the

battle of Otterbourne, and against all threats he refused to join the Lord of

the Isles in his invasion of Scotland which ended at the battle of Harlaw.

Murdoch married a daughter of MacLeod of Harris, and as that chief was fourth

in descent from Olaf, King of Man, while his wife was daughter of Donald Earl

of Mar, nephew of King Robert the Bruce, the blood of two royal houses was

thus brought to mix with that of the Mackenzie chiefs. The next chief, Alastair lonric, or the Upright, was among the

Highland magnates summoned by King James I. to meet him at Inverness in 1427.

With the others he was arrested, but, while many of them were executed for

their lawless deeds, he, being still a youth, was sent to school at Perth by

the King. During his absence his three bastard uncles proceeded to ravage

Kinlochewe, whereupon Macaulay, constable of Eileandonan, sent a secret

message to the young chief, who, leaving school forthwith, and hastening

north, summoned his uncles before him, and, on their proving recalcitrant,

made them "shorter by the heads," and so relieved his people of

their ravages. In similar case, Alexander, Lord of the Isles, had been sent

to Edinburgh by the King, but, escaping north, raised his vassals, burned

Inverness, and destroyed the crown lands. On this occasion the young chief of

the Mackenzies raised his clan, joined the royal army, and helped to

overthrow the island lord. Later, during the rebellion of the Earl of

Douglas, the Lord of the Isles, and Donald Balloch, against James II.,

Mackenzie again stood firm in loyalty to the Crown. For this in 1463 he

received a charter confirming him in his lands of Kintail, and in various

other possessions. So far these possessions had been held of the Earls of Ross,

but after the rebellion of the Earl of Ross in 1476, when he was compelled to

resign his earldom to the Crown, Mackenzie, who again had done loyal service,

became a crown vassal, and received a further charter of Strathconan,

Strathbran, and Strathgarve, which had been taken from the Earl. Of Alexander Mackenzie as a young man a romantic story is told. This

is to the effect that Euphemia Leslie, Countess Dowager of Ross, set her

fancy upon him, and desired him to marry her. Upon his refusal she turned her

love to hatred, and made him a prisoner at Dingwall. Then, by bribing his

page, she procured his ring, and sending it to Eileandonan induced Macaulay

the constable to yield up the castle to her. To secure his master’s freedom

Macaulay seized Ross of Balnagown, the countess’s grand-uncle. He was pursued

by the vassals of the Earl of Ross, and at Bealach na Broige a desperate

conflict took place. Macaulay, however, carried off his man, and presently,

managing to surprise Eileandonan, kept the countess’s governor and garrison,

along with Balnagown, in captivity until they were exchanged for the

Mackenzie chief. The conflict of Bealach na Broige, the Pass of the Shoe,

took place in 1452, and was so named from the Highlanders tying their shoes

to their breasts to defend themselves against the arrows of their opponents.

Many other romantic stories are told of the sixth chief. He was so far the

greatest man of his name, and when he died at the age of ninety in 1488 he

left the house of Mackenzie one of the most powerful clans in the north. Till now the succession to the Mackenzie family had depended always

upon a single heir. Alexander the sixth chief, however, was twice married. By

his first wife, Anna daughter of MacDougall of Dunolly, he had two sons, the

elder of whom succeeded him, and by his second wife, daughter of MacDonald of

Morar, he had one son, Hector who became ancestor of the Gairloch family. The seventh chief, Kenneth of the Battle, got his name from his part

in the battle of Blair na pairc, fought during his father’s lifetime near

their residence at Kinellan, a mile and a half from the modern spa of

Strathpeffer. To close the old family feud, Kenneth had married Margaret

daughter of John of Isla, Lord of the Isles, but John of Isla's nephew and heir,

Alexander of Lochalsh, making a feast at Balcony House, invited to it, among

other chiefs, Kenneth Mackenzie. On Mackenzie arriving with forty followers

he was told that the house was already full, but that a lodging had been

provided for him in the kiln. Enraged at the insult, he struck the seneschal to the ground, and left

the house. Four days later he was ordered with his father to leave Kinellan,

which they held as tenants of the island lord. Kenneth returned a message

that he would stay where he was, but would return his wife, and he

accordingly sent the lady back with the utmost ignominy. The lady had only

one eye, and he sent her on a one-eyed horse accompanied by a one-eyed

attendant and a one-eyed dog. A few days later, with two hundred men he besieged

Lord Lovat in his castle, and demanded his daughter Anne in marriage. Lord

Lovat and his daughter agreed, and ever afterwards Kenneth and the lady lived

as husband and wife. Meanwhile MacDonald had raised an army of sixteen hundred men, marched

northward through the Mackenzie lands, burning and slaying, and at Contin on

a Sunday morning set fire to the church in which the old men, women, and

children had taken refuge, and burned the whole to ashes. Then he ordered his

followers to be drawn up on the neighbouring moor for review. But Kenneth

Mackenzie, though he had only six hundred men, proved an able leader. He

succeeded in entangling his enemies in a peat bog, and when they were thrown

into confusion by a discharge from his hidden archers, fell upon them and put

them to flight. This invasion cost the Macdonalds the Lordship of the Isles,

which was declared by Parliament a forfeit to the Crown. Kenneth was on his way with five hundred men under the Earl of Huntly

to support James III. when news reached him of his father’s death, and Huntly

sent him home to see to his affairs, and so he missed taking part in the

battle of Sauchieburn, at which James fell. He was afterwards knighted by

James IV., and died in 1491. The eighth chief, Kenneth the Younger, was the son of the daughter of

the Lord of the Isles whom his father had so unceremoniously sent home. Along

with the young Mackintosh chief be was secured in Edinburgh castle by James

IV. as a hostage for his clan. After a time the two lads escaped, and reached

the Torwood. Here they met the Laird of Buchanan, then an outlaw, and he, to

secure the remission for his outlawry, surrounded the house at night with his

followers and demanded surrender. Mackenzie rushed out sword in hand, and was

shot with an arrow. This was in 1497. The next chief, John of Killin, Kenneth’s

half-brother, was considered illegitimate by many of the clan, though the

marriage of his mother had been legitimated by the Pope in the last year of

her husband’s life. The estates were seized by the young chief’s uncle,

Hector Roy, ancestor of the Gairloch family. But Lord Lovat procured a

precept of dare constat to protect his nephew’s interest, and Munro of

Fowlis, Lieutenant of Ross, proceeded to Kinellan to punish the usurper. As

Munro was returning, however, he was ambushed at Knockfarrel by Hector Roy,

and most of his men slain. Hector also defeated a royal force sent against

him by the Earl of Huntly in 1499. At last, however, his nephew John, with a

chosen band, beset him in his house at Fairburn, and set the place on fire.

Hector thereupon surrendered, and it was agreed that he should possess the

estates till the young chief was twenty-one years of age, whereupon

Eileandonan was delivered up to the latter. Both the chief John and his uncle

Hector Roy took part in the battle of Flodden, and, strange to say, both

escaped and returned home, though most of their followers fell. The chief was

taken prisoner by the English, but escaped through the kindness of the wife

of a shipmaster with whom he was lodged, and whose life had been saved in

dire extremity by a clansman in the Mackenzie country, who by killing and

disembowelling his horse and placing her inside during a terrible storm had

preserved her and her new-born child. Upon coming into possession of Eileandonan John Mackenzie made

Gilchrist MacRae constable of the castle, and before long the MacRaes had an

opportunity to show their mettle in this post. In 1539 MacDonald of Sleat

laid waste the lands of MacLeod of Dunvegan and his friend the Mackenzie

chief, killing the son of Finly MacRae, then Governor of Eileandonan.

Mackenzie thereupon despatched a force to Skye which made reprisals in

MacDonald’s country. MacDonald, hearing that Eileandonan was left

ungarrisoned, made a raid upon it with fifty birlinns. The only men in the

castle were the governor, the watchman, and Duncan MacRae. Presently the

governor fell, and MacRae found himself left with a single arrow. Watching

his chance, however, he shot MacDonald in the foot, severing the main artery,

and causing him to bleed to death. For the overthrow of the MacDonalds King

James conferred further possessions on Mackenzie. Old as he was, Mackenzie

fought for the child-Queen Mary at the battle of Pinkie, where he was taken

prisoner. His clansmen, however, showed their affection by paying his ransom.

John Mackenzie added greatly to the family estates in Brae Ross, and many a

quaint story is told of his shrewdness and sagacity before he died at the age

of eighty in 1561. Like so many of the early chiefs John had an only son, Kenneth of the

Whittle, so named from his dexterity with the skian dhu. He was among the

chiefs who helped Queen Mary to get possession of Inverness Castle when

refused by the governor, Alexander Gordon; and on the Queen’s escape from

Loch Leven, his son Colin was sent by the Earl of Huntly to advise her

retreat to Stirling till her friends could be gathered. The advice was

rejected, and Colin fought for the Queen at Langside. In Kenneth’s time a

tragedy occurred at Eileandonan. John Glassich, son and successor to Hector

Roy Mackenzie of Gairloch, fell under suspicion of an intention to renew his

father’s claim to be chief of the clan. Mackenzie therefore had him arrested

and sent to Eileandonan, and there he was poisoned by the Constable’s lady.

This chief married a daughter of the Earl of Atholl, and from his third son

Roderick was descended the family of Redcastle. The eleventh chief, One-Eyed Colin, was a special favourite at Court, and, like all his forebears, an able administrator of his own estate.

The Mackenzies were now strong enough to defy even the Earl of Huntly.

This great noble was preparing to destroy Mackintosh of Mackintosh, whose

wife was Mackenzie’s sister. Mackenzie sent asking that she should be treated

with courtesy, and Huntly rudely replied that he would "cut her tail

above her houghs." The Mackenzie chief was at Brahan Castle in delicate

health, but next day, his brother Roderick of Redcastle crossed the ferry of

Ardersier with four hundred clansmen, and when Huntly approached the

Mackintosh stronghold in the Loch of Moy he saw this formidable force

marching to intercept him. "Yonder," said one of his officers,

"is the effect of your answer to Mackenzie." The effect was so

unquestionable that Huntly found it prudent to retire to Inverness. In One-Eyed Colin’s time, about 1580, one of the most desperate feuds

in Highland history broke out, between the Mackenzies and the MacDonalds of

Glengarry, whose chief owned considerable parts of the neighbouring

territories of Lochalsh, Loch Carron, and Loch Broom. The feud began by

Glengarry ill-using Mackenzie’s tenants. It came to strife with the killing

of a Glengarry gentleman as a poacher, and before it was ended, in the next

chief’s time, it had brought about some of the most tragic events in Highland

history. This next chief Kenneth, twelfth of his line, was a man of singular

ability, who managed to turn the MacDonald and other feuds directly to the

increase of his house’s territory and influence. While Mackenzie was in

France, Glengarry’s son, Angus MacDonald and his cousins, committed several

outrages, slaying and burning Mackenzie clansmen, and, on the Mackenzies

retaliating, had the chief summoned at the Pier of Leith to appear before the

Council on pain of forfeiture. Through the prompt action of a clansman,

however, Mackenzie managed to return in time, turned the tables on his enemy,

and had him declared an outlaw, and ordered to pay him a very large sum by

way of damages. He then marched into Morar, routed the MacDonalds, and

brought back to Kintail the largest creagh ever heard of in the Highlands.

The MacDonalds retaliated with a raid on Kinlochewe, killing women and

children, and destroying all the cattle. Angus MacDonald also proceeded to

raise his kinsmen in the Isles against Mackenzie, and while the latter was

absent in Mull, seeking help from his brother-in-law, MacLean of Duart, he

made a great descent, burning and slaying, on Kintail. Then a notable incident occurred: Lady Mackenzie at Eileandonan had

only a single galley at home, but she armed it and sent it out to waylay

MacDonald. It was a calm moonlight night in November, with occasional showers

of snow, and Mackenzie’s galley lay in wait in the shadows below Kyle-rhea.

Presently as the tide rose a boat shot through. He let it pass, knowing it to

be MacDonald’s scout. Then they saw a great galley coming through, and made

straight for it, firing a cannon with which Lady Mackenzie had provided them.

In the confusion MacDonald’s galley ran on the Cailleach rock and every one

of the sixty men on board, including Angus MacDonald himself, was slain or

drowned. Mackenzie also took and destroyed Glengarry’s stronghold, Strome

Castle. Then Allan Dubh MacDonald, Glengarry’s cousin, made a raid on

Mackenzie’s lands of Brae Ross, and on a Sunday morning, while all the people

were at divine service in the church of Cillechroist, set fire to the fane,

and burnt men, women, and children to ashes, while his piper marched round

the building, drowning their shrieks with a pibroch which ever since, under

the name of " Cillechroist," has remained the family tune of

Glengarry. As the MacDonalds returned home they were pursued by the

Mackenzies, who came up with them, as morning broke, on the southern ridge of

Glen Urquhart above Loch Ness. Like Bruce on a famous occasion, Allan Dubh

divided his men again and again, but the Mackenzies were not thrown off his

track, and presently he found himself alone with Mackenzie of Coul at his

heels. In desperation he made for the fearful ravine of the Aultsigh Burn,

and sprang across. Mackenzie followed, him, but missed his footing, slipped,

and hung suspended by a hazel branch. At that MacDonald turned, hewed off the

branch, and sent his pursuer to death in the fearful chasm below. He himself

then escaped by swimming across Loch Ness. The feud was ended by Mackenzie,

in 1607, obtaining a crown charter of the MacDonald lands in Loch Aish, Loch

Carron, and elsewhere, for which be paid MacDonald ten thousand merks, while

MacDonald agreed to hold his other lands off him as feudal superior. Another great addition to Mackenzie’s territories occurred in the time

of the same chief. Torquil MacLeod of the Lews had married as his second wife

a daughter of John Mackenzie of Killin, but he disinherited her son Torquil

Cononach, and adopted his eldest son by a third wife as his heir. Torquil

Cononach was protected by Mackenzie, and recognised as the heir by the

Government, and upon his half-brother raiding Mackenzie’s territory the

latter obtained letters of fire and sword against him. At the same time

Torquil Cononach, his two sons being slain, made over his rights in the

island to Mackenzie. Then came the attempt of the Fife adventurers, who

obtained a grant of the Lews and tried to colonise and civilise it. After

much disturbance they were ruined and driven out, and a later effort of the

Earl of Huntly fared no better. Mackenzie then in virtue of Torquil

Cononach’s resignation, had his possession of the Lews confirmed by charter

under the Great Seal, and, proceeding there with seven hundred men, brought

the whole island to submission. In recognition of this service to law and

order James VI. in 1609 conferred a peerage on the chief, as Lord Mackenzie

of Kintail. Only a small band of MacLeods kept up resistance in the Lews, and this

was brought to an end in a dramatic way. On the death of Lord Mackenzie in

1611 he was succeeded by his son, Colin the Red. During his minority, the

estates were managed by Sir Roderick Mackenzie of Coigeach. The remnant of

the MacLeods had held out on the impregnable rock of Berrissay for three

years when the tutor of Kintail gathered all their wives, children, and

relations, placed them on a tidal rock within sight of MacLeod’s stronghold,

and declared that he would leave them there to drown unless MacLeod instantly

surrendered. This MacLeod did, and so the last obstacle to Mackenzie’s

possession was removed, and "The inhabitants adhered most loyally to the

illustrious house, to which they owed such peace and prosperity as was never

before experienced in the history of the island." This latest addition vastly increased the possessions of the Mackenzie

chief, who was moreover a great favourite at the court of James VI., and in

1623 he was created Earl of Seaforth and Viscount Fortrose. The Earl lived in

his castle of Chanonry in the Black Isle in great magnificence, making a

state voyage with a fleet of vessels round his possessions every two years.

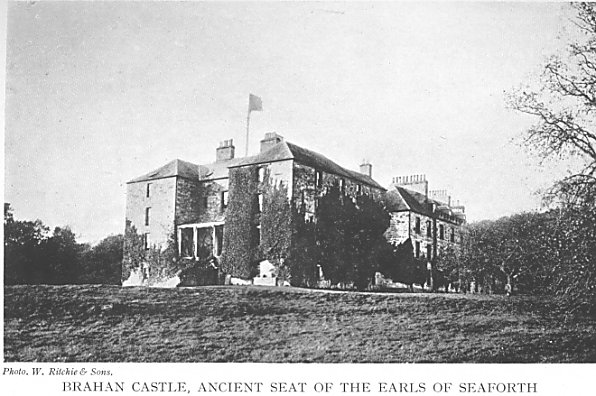

He built the castle of Brahan and Chanonry while his tutor, Sir Roderick of

Coigeach, ancestor of the Earl of Cromartie, built Castle Leod. His brother George, who succeeded as second Earl and fourteenth chief

in 1633, played a very undecided and self-seeking part in the civil wars of

Charles I., appearing now on the Covenant’s side and now on the King’s, as

appeared most to his advantage. He fought against Montrose at Auldearn, but

afterwards joined him. Upon this he was excommunicated and imprisoned by the

Covenanters for a time, and he died while secretary to King Charles II. in

Holland in 1651, upon news of the defeat of the young King at Worcester. His eldest son, Kenneth Mor, the third Earl, joined Charles II. at

Stirling in his attempt for the crown, and after the defeat at Worcester had

his estates forfeited by Cromwell and remained a close prisoner till the

Restoration, when he was made Sheriff of Ross. He died in 1678. His eldest son, Kenneth Og, the fourth Earl, was made a member of the

Privy Council and a companion of the Order of the Thistle by James VII. It was the time of the later Covenanters, and two of Seaforth’s

relatives had the chief direction of affairs in Scotland—Sir George Mackenzie

of Tarbat, afterwards first Earl of Cromartie, as Lord Justice-General, and

Sir George Mackenzie of Rosehaugh as Lord Advocate. Both were, in private,

amiable and learned men, but as officials they showed little mercy to rebels,

as they considered the upholders of the Covenant. At the Revolution the Earl accompanied King James to France, and after

taking part in the siege of Londonderry and the battle of the Boyne, was

created a Marquess at the exiled court. But the fortunes of his house had

reached their climax, and he died an exile. It was his only son, William Dubh, the fifth Earl, who took part in

the Earl of Mar’s rebellion in 1715. As a Jacobite he raised three thousand

men, and fought at the battle of Sheriffmuir. For this his earldom and

estates were forfeited. Four years later, on the breaking out of war with

Spain, he sailed with the Spanish expedition, and landed in Kintail, but was

wounded and defeated by General Wigbtman at Glenshiel. During his exile

afterwards in France the Government completely failed to take possession of

his estates. These were defended by his faithful factor, Donald Murchison,

who had been a colonel at Sheriffmuir, and who now skilfully kept the passes

and collected the rents, which he sent to his master abroad. At last, in

1726, on his clansmen giving up their arms to General Wade, they and Seaforth

himself received a pardon. Sad to say, on the chief returning home he treated

Murchison with rude ingratitude, and the factor died of a broken heart. The Seaforth title remained under attainder, and the Earl’s son

Kenneth, the eighteenth chief, who succeeded in 1740, remained known by his

courtesy title as Lord Fortrose. The estates were purchased on his behalf for

£26,000, and on the outbreak of the Jacobite rebellion of 1745 he remained

loyal to the Government. His kinsman, the Earl of Cromartie, who had then

probably more influence with the clan, took the side of the Prince with a

considerable number of men, and in consequence lay under sentence of death

for a time. It was one of the name, Roderick Mackenzie, son of a goldsmith in

Edinburgh, who, on being cut down in Glen Morriston, called out, "You

have slain your Prince! " and from his likeness to Charles threw the

scent off his royal master for a space, and so helped his escape. Lord Fortrose died in 1761. His only son Kenneth, known as "the

little Lord," was created Earl of Seaforth in the peerage of Ireland in

1771. Seven years later he raised a regiment of 1,130 men, but on his way

with it to India died near St. Helena in 1781. The Earl was without a son, and in 1779, being heavily embarrassed,

had sold the Seaforth estates to his cousin and heir male, Colonel Thomas F.

Mackenzie Humberston. The father of the latter was a grandson of the third

Earl, and had taken the name Humberston on inheriting the estates of his

mother’s family. Colonel Humberston had been chief for no more than two years

when he was killed in an attack by the Mahrattas on the "Ranger"

sloop of war out of Bombay. He was succeeded by his brother Francis Humberston Mackenzie, as

twenty-first chief. In the war with France this chief raised two battalions

of his clansmen, which were known as the Ross-shire Buffs, now the Seaforth

Highianders, and as a reward was made lord-lieutenant of Ross-shire, and a

peer of the United Kingdom, with the title of Lord Seaforth. As Governor of

Barbadoes he put an end to slavery in that island, and altogether, though

very deaf and almost dumb, achieved a great reputation by his abilities.

These drew forth from Sir Walter Scott an eloquent tribute in his Lament

for the last of the Seaforths: In vain,

the bright course of thy talents to wrong, It was in

the person of this chief that the prediction of the Brahan Seer was

fulfilled. This prediction, widely known throughout the Highlands for

generations before it was accomplished, declared that when a deaf Mackenzie

should be chief, and four other heads of families should have certain

physical defects, the house of Seaforth should come to an end. So it

happened. At this time Sir Hector Mackenzie of Gairloch was buck-toothed;

Chisholm of Chisholm was hare-lipped; Grant of Grant was half-witted; and

MacLeod of Raasay was a stammerer. So it came about. Lord Seaforth’s four

sons all died before him unmarried; from his own indulgence in high play he

was forced to sell, first a part of Lochalsh, and afterwards Kintail and

other estates, and when he died the remainder passed to his eldest daughter,

Lady Hood, then a widow. This lady afterwards married Stewart of Glasserton,

a cadet of the house of Galloway, himself distinguished as a member of parliament,

governor of Ceylon, and Iord High Commissioner to the lonian Islands. He took

the name of Mackenzie, and at his lady’s death at Brahan Castle in 1862, she

was succeeded in possession of the estates by her eldest son Keith William

Stewart Mackenzie, of Seaforth. Meanwhile

the chiefship of the clan passed to James Fowler Mackenzie of Allangrange, as

lineal representative of Simon Mackenzie of Lochshin, seventh son of Kenneth,

first Lord Mackenzie. It is interesting to note that the eldest son of Simon

Mackenzie was Sir George Mackenzie of Rosehaugh, Lord Advocate, author of the

famous Institutes of Scots Law, founder of the Advocate’s Library, and

well known as" the Bluidy Mackenzie" of Covenanting folklore. Sir

George’s sons, however, all died without male heirs. Through his daughter

Agnes, who married the Earl of Bute, his estates passed to that family, and

the succession was carried on by his younger brother, Simon. Since the death

of Allangrange some years ago the title to the chiefship has been uncertain.

It probably remains with a descendant of the Hon. Simon Mackenzie of Lochshin

by his second wife, until recently Mackenzie of Dundonnell; but several of

the sons of this family are untraced. Besides this line there are many cadet

branches of the ancient house, and it remains for one of those interested to

trace out the actual chiefship. In several instances, such as those of the

houses of Gairloch and of Tarbat, the latter of whom became Earls of

Cromartie, the history is only less romantic than that of the chiefs

themselves; but for these the reader must be referred to the work already

quoted, The History of the Clan Mackenzie, by Alexander Mackenzie,

published in Inverness in 1879. Septs of

Clan MacKenzie: Kenneth, Kennethson, MacBeolain, MacConnach, MacIver,

MacIvor, MacKerlich, MacMurchie, MacVinish, MacVanish, Murchison, Murchie. |